The stateless architecture pattern describes a fundamental (and possibly the most important) design principle for cloud-based applications, in which an application does not save any state between individual requests from a client.

Each request is processed completely independently of the requests already made, and all required values are provided as parameters.

Problem and Motivation

In modern, distributed applications, for example, in microservice architectures, scalability, partition tolerance, and maintainability are at the heart of software architecture. Stateful applications pose a particular challenge in these respects. They store a client-dependent state between the individual requests of a client, which must be managed. In an e-commerce application, for example, this state contains the items a user has placed in their shopping cart or the progress in a multipage form dialog.

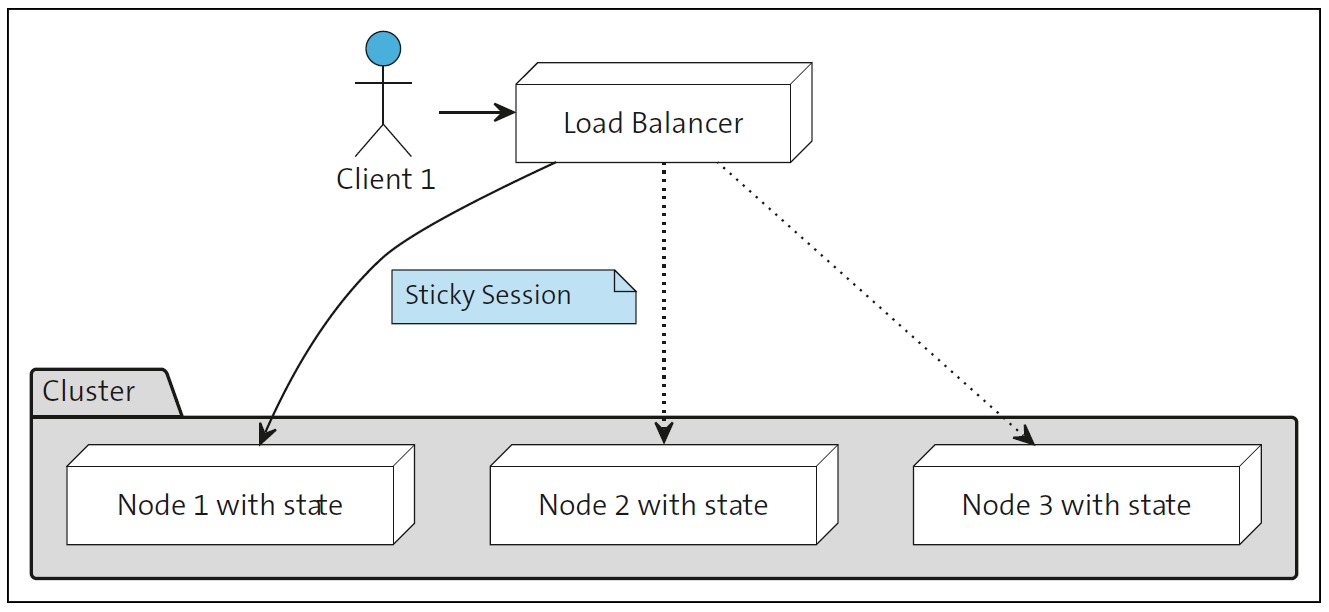

If you only have one instance of the application, managing states can be performed in the application’s main memory. However, if multiple instances are used, as is common in modern cloud environments, the effort required to manage states increases and makes horizontal scaling of the application more difficult. The state must either be synchronized between the instances, or individual clients are bound to dedicated servers in what are called sticky sessions so that their states don’t need to be replicated. Such a configuration can be implemented using a load balancer, as shown in this figure.

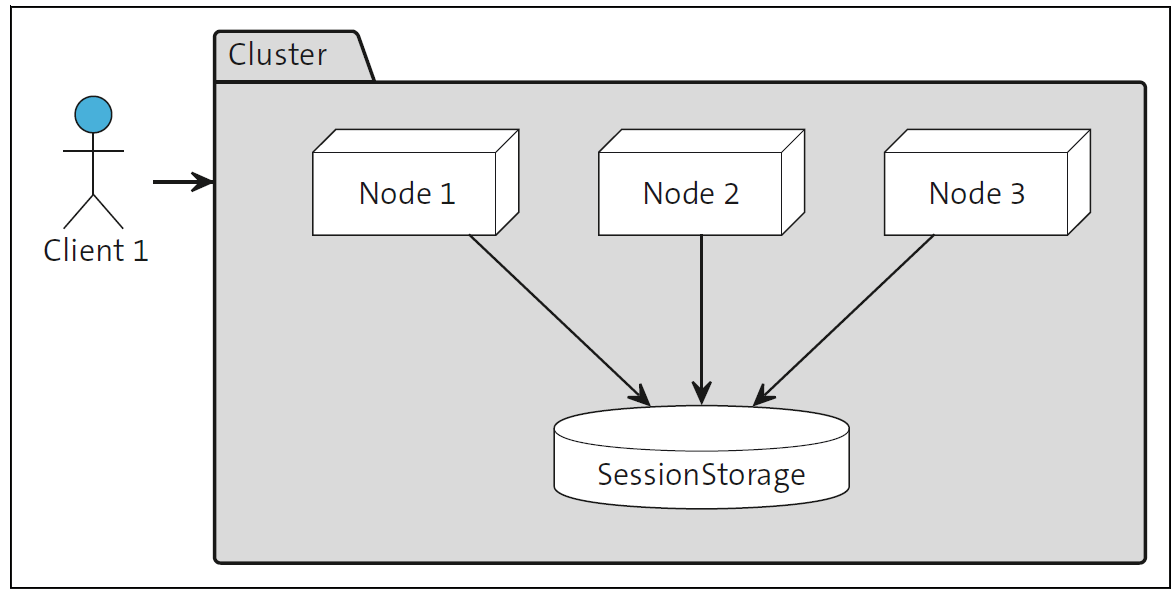

As shown in the next figure, databases are also often used to store a state, such as a session state for clients. Therefore, a status no longer requires explicitly synchronization between the individual nodes, but instead, a new dependency on a database is created.

These types of dependencies increase the complexity of the application and can cause problems in the event of system failure or during peak loads. In this example, the load on the application and the data volume in the database automatically increase as the number of simultaneous clients increases. The possibilities for scaling are restricted.

Solution

Stateless applications do not have a user-dependent status and therefore do not require status management. The term stateless does not refer to the complete absence of data storage, but rather to the fact that no user-dependent data is stored.

The following distinctions are important for differentiation:

Application State

The application state is the status that is held on the server side for a client and contains information about the current context of that client. These are, for example, the shopping carts of customers.

Resource State

The resource state is the status of a resource managed by the server, which is independent of any interaction by a client. This state could be item data or stock levels, for example. Of course, a client can place an order, for example, and the stock level changes, but this data is not linked to a client.

Stateless applications do not use the application state.

Stateless Despite a Status in the Database?

Applications that save a user-dependent status in a database (e.g., in a session database) are often referred to as “stateless” as well because they do not save any status within the application instance. Nevertheless, these applications have an application state that must be managed and therefore are not stateless in the strictest sense of the word.

Each request is considered a separate, independent transaction, and no user state is stored between requests. All required parameters must be transferred with each call.

This process corresponds to the equally stateless HTTP protocol, in which each HTTP request is also independent and autonomous. No reference to previous requests or contexts exists. This statelessness can be achieved via cookies or parameters, but then, these elements must also be passed again with each request. For stateless applications, the client is responsible for saving session-dependent data.

For stateless applications that require authentication, this means, for example, that the relevant authentication information must be transmitted again with each request.

Let’s look at two HTTP requests to illustrate this point. The listing below shows a stateful communication with the server. The first request performs a search and returns a result set and a cookie in the corresponding HTTP header. If the client wants to jump to the second page, the client sends a request to a generic URL that contains the returned cookie in the Cookie HTTP header. This session cookie identifies the client to the server so that the corresponding data can be sent back.

# Search

GET https://www.google.com/search?q=Golang

# Query the next page

GET https://www.google.com/nextPage

Cookie: ...

# Query the next page

GET https://www.google.com/nextPage

Cookie: ...

The communication shown below, on the other hand, is stateless. The client provides all information with each request, and the server can respond to the request accordingly.

# Stateless requests

GET https://www.google.com/search?q=Golang&page=1

GET https://www.google.com/search?q=Golang&page=2

GET https://www.google.com/search?q=Golang&page=3

A stateless architecture benefits from the following advantages:

- The application can quite easily be scaled horizontally.

- The caching of data is easier since all information is included with the individual requests, and these requests can therefore be differentiated.

- The application architecture is simpler compared to stateful solutions and therefore easier to maintain.

- No replication between individual application nodes is required.

- Fault tolerance is high for failures of individual nodes, as each instance can seamlessly take over the tasks of a failed node.

- Deployment can be carried out flexibly because no status data requires synchronization.

Sample Solution

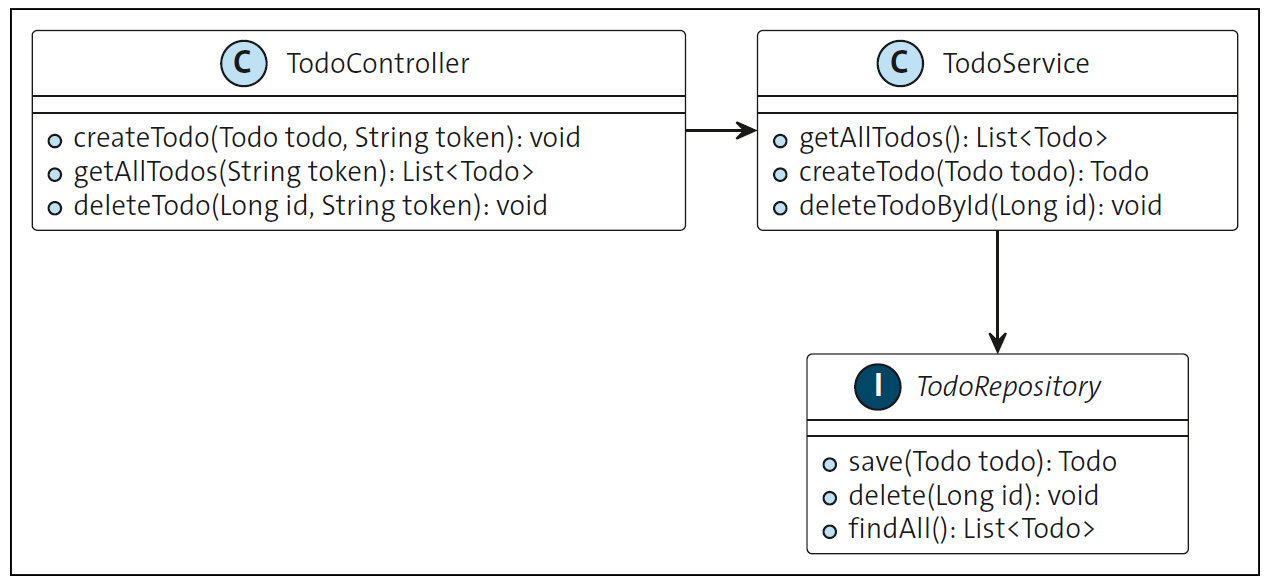

As an example, let’s take a look at an application for to-do lists that access a database in the background. A user-dependent status or session is not used. The client must reauthenticate with a security token for each query, and the data is saved as resources for all clients.

In our example, authorization credentials in the form of a token are provided with every request within the HTTP header. The token typically contains all the information required by the server to authenticate the user. In the case of JSON web tokens (JWT), a basic validation of the token can also be carried out using a contained signature without access to an external service.

Although the state of an authorization is used within the header, the application itself is not stateful in the classic sense. As long as the server does not store any session information about the client and all relevant information is contained in the requests (including the token), the application is still considered stateless.

However, if the server saves the state or information about the token in a database (e.g., to manage a revocation list), then the application becomes stateful.

This figure shows a class diagram for a Spring-based application.

The application has a stateless HTTP interface that can be used to create, display, and delete Todo objects. A new entry can be created with the HTTP request shown in the listing below. In this context, an important step is that the request is given a token for authentication since no HTTP session is established.

# Add a new entry

POST http://localhost:8082/api/todos

Authorization: Bearer xxx

Content-Type: application/json

{

"title": "Cleanup",

"completed": false

}

The code on the server side must check the authentication again for each call. In the example shown below, this check is implemented separately in each method. Of course, an interceptor or filter could and should be used in this case.

@PostMapping

public ResponseEntity<Todo> createTodo(@RequestBody Todo todo,

@RequestHeader("Authorization") String token) {

validateToken(token); // JWT validation

Todo createdTodo = todoService.createTodo(todo);

return ResponseEntity.status(HttpStatus.CREATED).body(createdTodo);

}

The remaining HTTP requests and controller implementations are similar, as shown here.

# Query all existing todo entries

GET http://localhost:8082/api/todos

Authorization: Bearer xxx

###

# Delete an existing entry

DELETE http://localhost:8082/api/todos/1

Authorization: Bearer xxx

When To Use the Stateless Architecture Pattern

Some examples of when to use the pattern include the following:

- The server does not have or should not have a user-dependent state.

- Good horizontal scalability of the application should be given.

- The environment must react to changing load requirements by dynamically starting additional instances.

- Reliability should be achieved across multiple instances, and the failure of individual instances should be insignificant.

- Simple structures in the application should increase maintainability.

Consequences

The use of the stateless architecture pattern has the following consequences:

- The application is easily scalable.

- Fault tolerance is greater since individual instances can be replaced without any problems.

- Maintenance is easier because the application is less complex.

- Applications designed with this pattern can be easily deployed in cloud technologies, for example, in container environments (with Kubernetes) and in serverless environments.

- Overhead is greater for individual requests since all parameters must always be transferred.

- No client-dependent status management is necessary. Workarounds may be required for session management, for instance, if session resources are to be created.

- No session support is available.

Conclusion

The stateless architecture pattern removes the complexity of managing user-specific data on the server and enables applications to scale, recover, and evolve with far fewer constraints. By shifting state handling to the client and requiring each request to be complete and independent, systems gain the flexibility and resilience needed in modern cloud environments. While this approach introduces some overhead and requires careful handling of authentication and session-like workflows, the trade-offs are well worth it for distributed, scalable architectures.

Editor’s note: This post has been adapted from a section of the book Software Architecture and Design: The Practical Guide to Design Patterns by Kristian Köhler. Kristian is a software architect and developer with a passion for solving problems using efficient, well-structured software. He is the managing director of Source Fellows GmbH.

This post was originally published 12/2025.

Comments